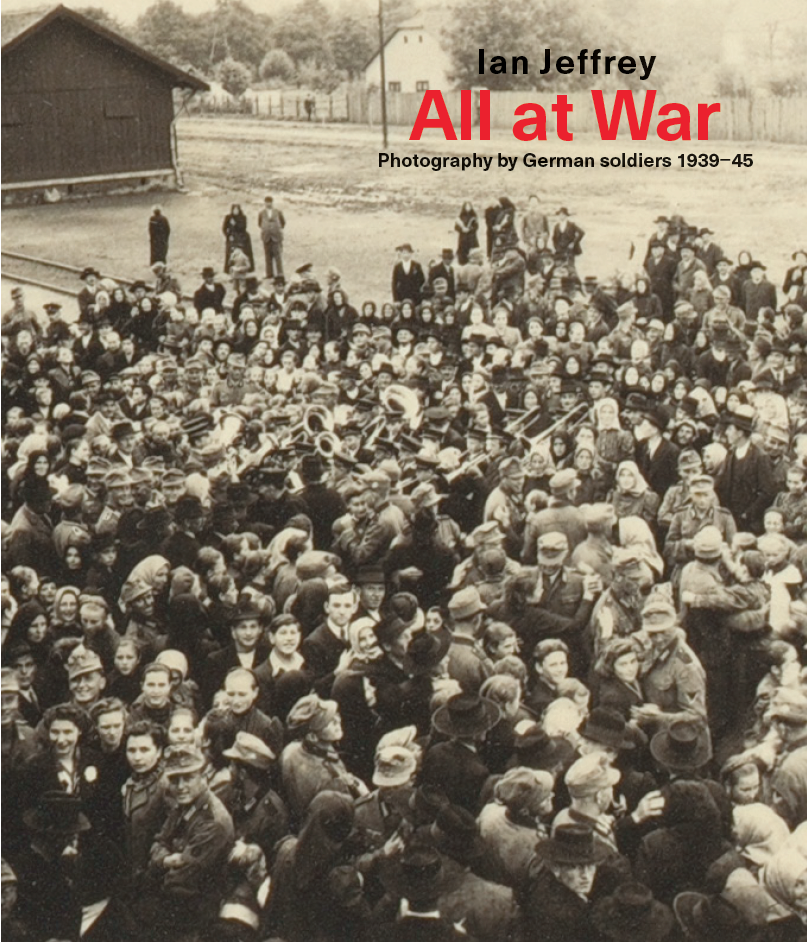

Ian Jeffrey on War Photography

Ian Jeffrey is an English art historian, writer and curator. He is the author of All At War, a book published by Ludion, which gives insight into the lives of the German soldiers during WWII through the lens of the soldiers themselves. In this interview Jeffrey tells us all about wartime photography during WWII, and explains how we should look at these pictures.

What makes German soldiers’ photography distinct?

They may have owned Leica and Rolleiflex cameras using 35mm and 120 film typical of the 1930s but they were taking pictures under unusual conditions. Photography in the 1930s normally took place locally, in the context of small towns and camera clubs. Soldiers, on the other hand, were on the move and dependent on the Feldpost for the handling of their negatives and prints. They saw their results as small-scale prints, weeks after the pictures had been taken, by which time they had moved on. What they were receiving back from the developers were sets of miniatures that could be shuffled, juxtaposed and re-arranged like packs of cards. Few of these collections were fully ordered in the first place. A positive aspect of this kind of soldiers’ photography is that it was full of surprises, of unintended and hidden details – which made it worth scrutinising when it came back from the printers. It was also like silent film, to be completed or complemented by commentaries and observations.

They may have owned Leica and Rolleiflex cameras using 35mm and 120 film typical of the 1930s but they were taking pictures under unusual conditions. Photography in the 1930s normally took place locally, in the context of small towns and camera clubs. Soldiers, on the other hand, were on the move and dependent on the Feldpost for the handling of their negatives and prints. They saw their results as small-scale prints, weeks after the pictures had been taken, by which time they had moved on. What they were receiving back from the developers were sets of miniatures that could be shuffled, juxtaposed and re-arranged like packs of cards. Few of these collections were fully ordered in the first place. A positive aspect of this kind of soldiers’ photography is that it was full of surprises, of unintended and hidden details – which made it worth scrutinising when it came back from the printers. It was also like silent film, to be completed or complemented by commentaries and observations.

How should we look at wartime pictures?

Wartime pictures were seldom intended as discrete items to be looked at for their own sakes. It was only the most avant-garde material that dealt with ideas and discouraged mere conversation. The general run of pictures can be understood as visual elements supporting talk about sites, events and identities. Pictures that had been printed in home towns and returned would have been discussed with comrades and later on with families. In authors’ albums pictures are often captioned, sometimes with comments – bits of speech. Wartime pictures were mostly anecdotal.

What does a normal wartime picture look like?

A typically normal picture might feature a group of soldiers eating from mess tins around one of those wheeled boilers you see in the early part of the campaign in the USSR. These are group portraits in which the photographer would probably have been able to identify most of those present. Soldiers kept track of events so that they could recount their campaigns. They might also have taken landscapes featuring churches to show that they had reached Smolensk, for example – which had a prominent Cathedral overlooking the city. Normal pictures disclosed bits of narrative. Several photographers, very few considering the many thousands in the German armies, didn’t take normal pictures and tried to distance themselves from local and familiar events, from the small talk of the campaign.

Wartime pictures were seldom intended as discrete items to be looked at for their own sakes. It was only the most avant-garde material that dealt with ideas and discouraged mere conversation. The general run of pictures can be understood as visual elements supporting talk about sites, events and identities. Pictures that had been printed in home towns and returned would have been discussed with comrades and later on with families. In authors’ albums pictures are often captioned, sometimes with comments – bits of speech. Wartime pictures were mostly anecdotal.

What does a normal wartime picture look like?

A typically normal picture might feature a group of soldiers eating from mess tins around one of those wheeled boilers you see in the early part of the campaign in the USSR. These are group portraits in which the photographer would probably have been able to identify most of those present. Soldiers kept track of events so that they could recount their campaigns. They might also have taken landscapes featuring churches to show that they had reached Smolensk, for example – which had a prominent Cathedral overlooking the city. Normal pictures disclosed bits of narrative. Several photographers, very few considering the many thousands in the German armies, didn’t take normal pictures and tried to distance themselves from local and familiar events, from the small talk of the campaign.

Is there a turning point in the history of the war – in photographic terms at least?

Yes, the invasion of the USSR in the summer of 1941. The army assembled for the invasion was enormous, compared to those used in Poland and France. It featured a lot of support troops, working in telephone and radio communications, in administration and in supplies. Many of these were older men, who often served as drivers, and civilian technicians and specialists called up especially for the event. Not all of them were committed warriors, and some were even indifferent to the fighting and to military life. There seem to have been a lot of photographers amongst these groups. They may have worked previously as cinematographers or as designers and brought with them unfamiliar skills and outlooks – and a degree of scepticism about the national project.

Is there any aspect of wartime photography that was new – in a wider sense?

Yes, there was a preoccupation with gesture. Gesture had been on the agenda since Erich Salomon c. 1930. Cartier-Bresson and Capa in the 1930s took gestural pictures. It becomes especially evident in the war years. To begin with, though, photography was associated with formalized domestic rituals and group portraits. Soldiers liked to pose for each other but candid picturing became more usual as the going got harder. Spontaneous gestures were evocative and revealing, almost autographic – and far beyond the descriptive power of words. Accurate gestures had calligraphic qualities and they were definitive, expressive things in themselves – even if they were of no more than someone resting or bent over a newspaper. To attend to gesturing as a poetic expression of being was one way of bypassing or seeing through the harsh surfaces of the war.

Yes, the invasion of the USSR in the summer of 1941. The army assembled for the invasion was enormous, compared to those used in Poland and France. It featured a lot of support troops, working in telephone and radio communications, in administration and in supplies. Many of these were older men, who often served as drivers, and civilian technicians and specialists called up especially for the event. Not all of them were committed warriors, and some were even indifferent to the fighting and to military life. There seem to have been a lot of photographers amongst these groups. They may have worked previously as cinematographers or as designers and brought with them unfamiliar skills and outlooks – and a degree of scepticism about the national project.

Is there any aspect of wartime photography that was new – in a wider sense?

Yes, there was a preoccupation with gesture. Gesture had been on the agenda since Erich Salomon c. 1930. Cartier-Bresson and Capa in the 1930s took gestural pictures. It becomes especially evident in the war years. To begin with, though, photography was associated with formalized domestic rituals and group portraits. Soldiers liked to pose for each other but candid picturing became more usual as the going got harder. Spontaneous gestures were evocative and revealing, almost autographic – and far beyond the descriptive power of words. Accurate gestures had calligraphic qualities and they were definitive, expressive things in themselves – even if they were of no more than someone resting or bent over a newspaper. To attend to gesturing as a poetic expression of being was one way of bypassing or seeing through the harsh surfaces of the war.