Shin Hanga means ‘new prints’ and depicts harmoniously balanced designs, printed with woodblocks on high quality paper using the brightest and finest pigments and published in small editions. Our latest publication sets out to explore this early 20th-century Japanese art movement, which integrated Western elements with the old values of traditional woodblock prints. In the book you’ll find a unique selection from two Dutch private collections, the Royal Museum of Arts and History in Brussels and several exceptional items from the family collection of the publisher Watanabe Shōzaburō, the most important publisher of Japanese prints of the 20th century.

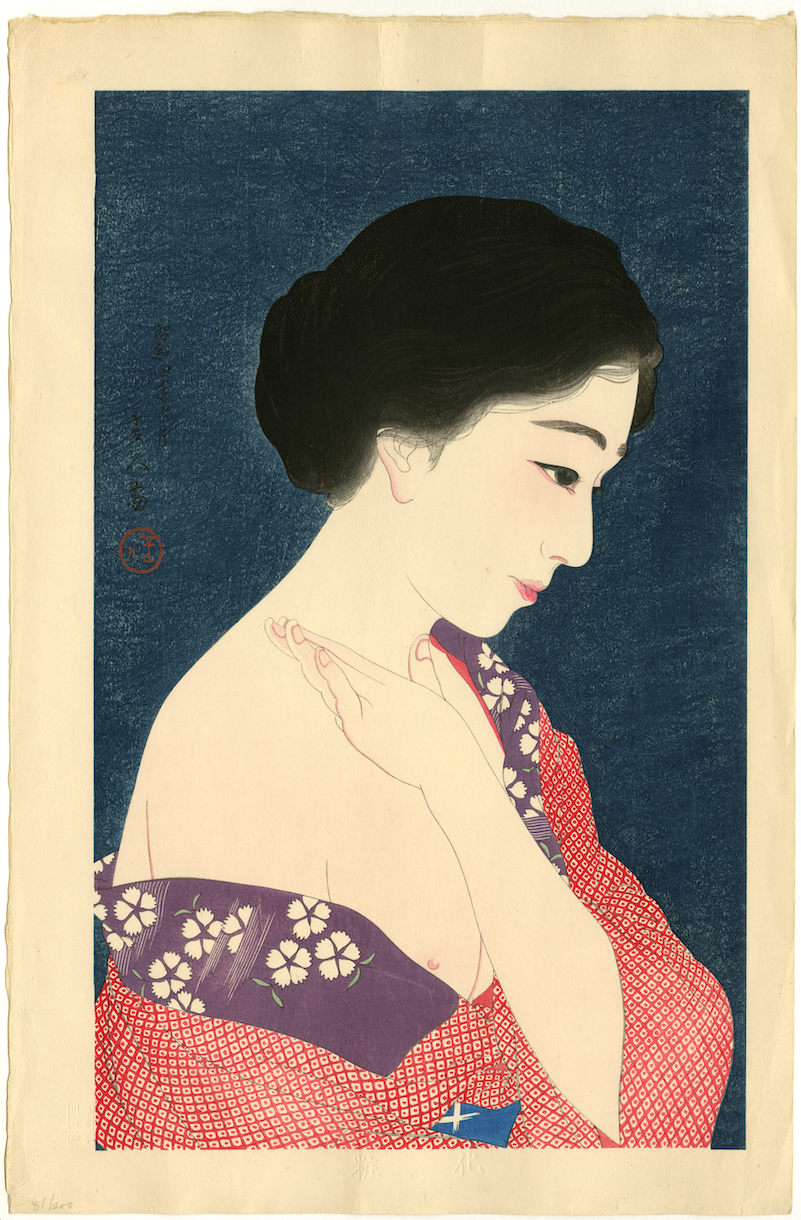

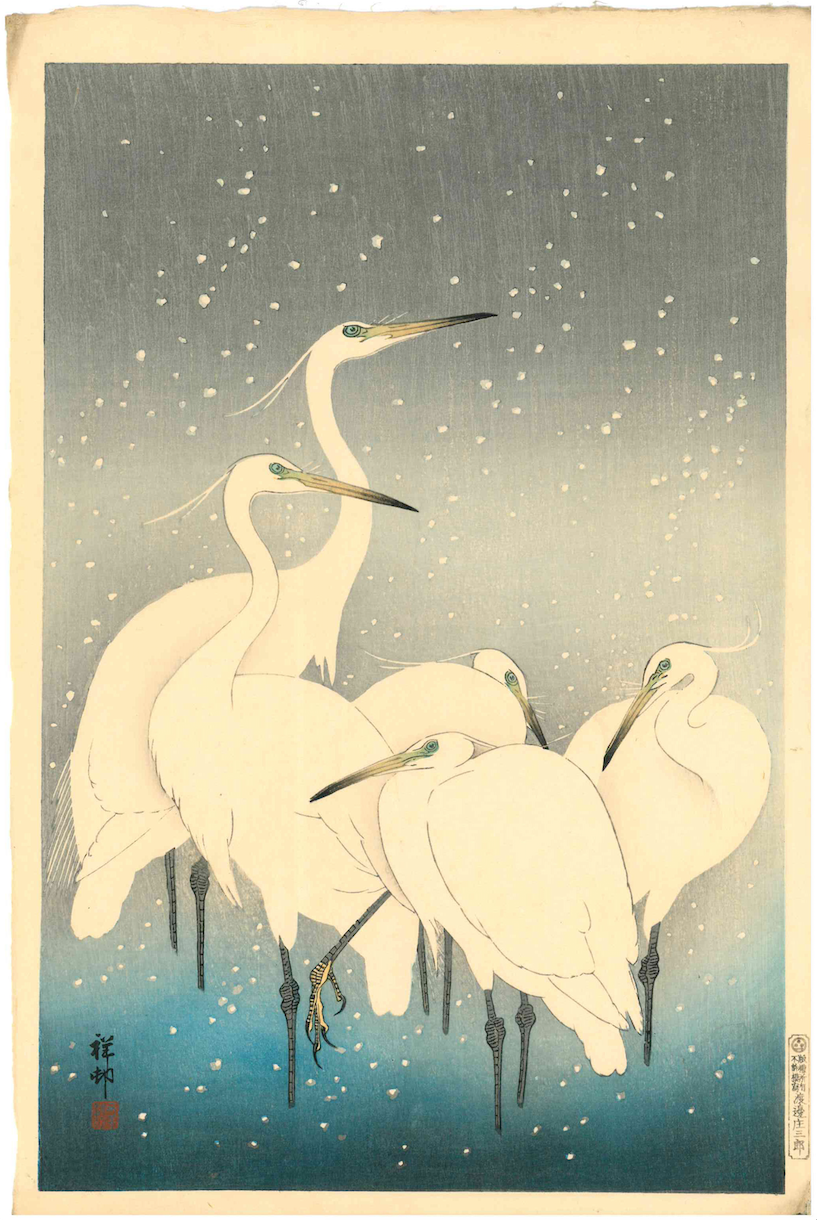

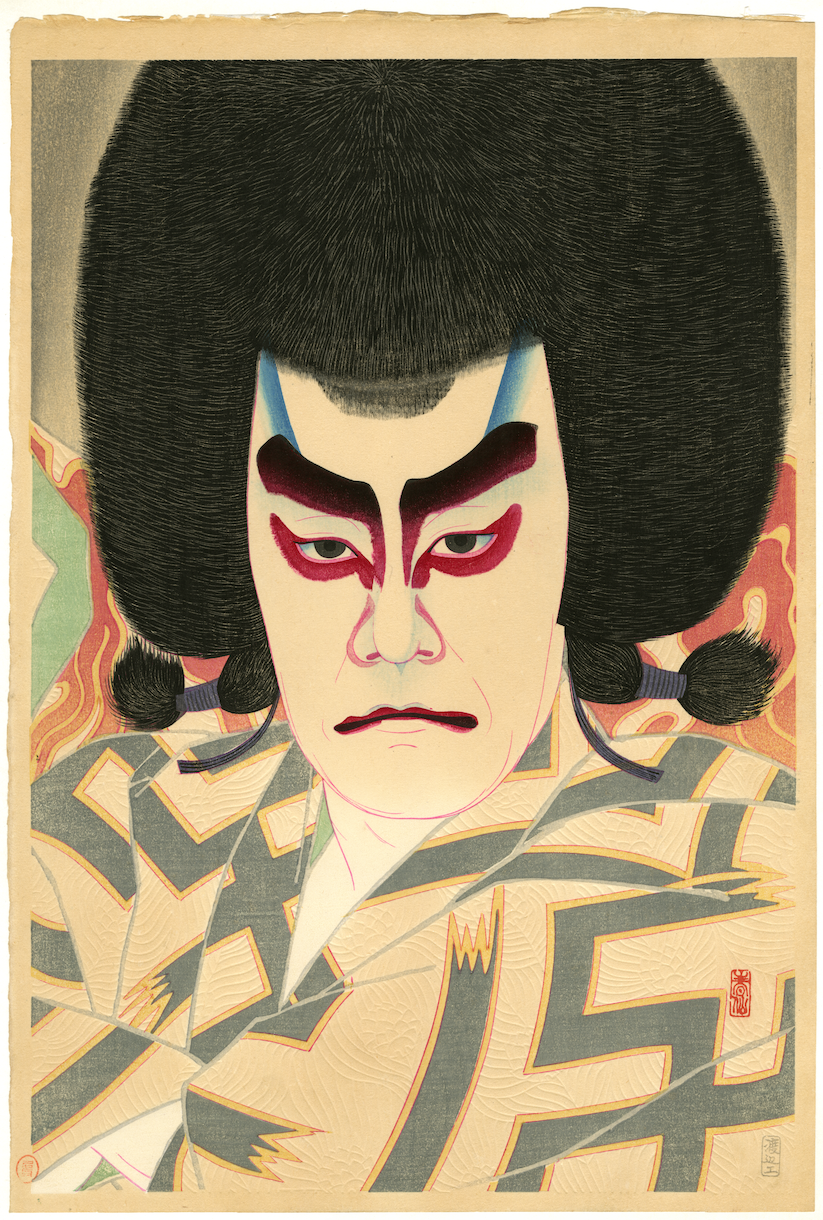

The Shin Hanga movement flourished from around 1915 to 1942, resuming on a smaller scale after the Second World War through the 1950s and 1960s. Inspired by European Impressionism the artists introduced the effects of light and the expression of individual moods but remained focused on strictly traditional Japanese themes of landscapes (fukeiga), beautiful women (bijinga), kabuki actors (yakusha-e), and birds-and-flowers (kachō-e).

The movement gave a new impetus to the traditional system of ukiyo-e, a collaboration in which the artist, carver, printer and publisher shared the work. Shin hanga however, emphasized the role of the publishers or hanmoto such as Watanabe, Doi, Kawaguchi & Sakai, Unsodo, Shobido and more. Watanabe Shosaburo feared the erosion of traditional skills and woodcutting techniques and came up with the term in 1915 because he wanted to separate shin hanga from the commercial mass art that had been ukiyo-e. He wanted the artist to combine traditional Japanese techniques with elements of contemporary Western painting and became uniquely successful in promoting these works, first in the expat community in Japan and from 1910 on auctions in the United States, thus giving his artists financial security. He is widely regarded as the founder of the movement.

The new prints were aimed at a Western audience and fed an interest in a nostalgically romanticized Japan. There was not much domestic market for shin hanga prints in Japan. Ukiyo-e had been considered by the Japanese as mass products, as opposed to the European view of ukiyo-e as fine art during the climax of Japonisme. The themes in both ukiyo-e (images of a floating world) and shin hanga overlapped and aesthetically the distinction seemed superficial. Yet shin hanga prints were much more of a luxury product and took far more effort, far more color printings or individual woodblacks, (natural) dyes and heavier paper. The success with admirers and collectors from Europe and the United States further anchored Western influence and techniques.

The death of Kawase, Watanabe's favourite artist, in 1957 and his own death in 1962 marked the beginning of the end of the Shin-hanga movement. By that time the sasoku hanga or creative prints had gained a lot in popularity, plus in 1952 the American occupation of Japan ended which also meant a decrease in demand for shin hanga.